The Fugitive Slave Act was passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, a series of bills intended to diffuse escalating tensions between slave-holding and non-slave-holding states. As the eventual Civil War proved, the compromise did little to assuage the animosity. But the Fugitive Slave Act — which required both officials and citizens of free states to cooperate in the capture and return of people who had escaped from slavery — was particularly repugnant to abolitionists. When Shadrach Minkins escaped to Boston in the spring of 1850, he became one of the first enslaved people to “test” the new act. Fortunately, he found overwhelming support in the New England abolitionist community, who staged a daring rescue and facilitated Minkins’ ultimate escape to Canada.

Shadrach Minkins was born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia in approximately 1814. He worked for slaveholder Thomas Glenn at the Eagle Tavern before being sold to a string of owners ending with John DeBree.

Not much is known about Minkins’ initial escape from slavery, but he most likely departed Norfolk on a northbound ship to Boston in the spring of 1850. He found work at the Cornhill Coffee House and Tavern, living under the pseudonym Frederick Minkins.

Nine months later, a Norfolk constable set out to locate Minkins on DeBree’s behalf. Under the power of the Fugitive Slave Law, Caphart enlisted the help of the U.S. Commissioner and federal marshals in Boston to arrest Minkins and return him to Virginia.

After ordering coffee at the Cornhill Coffee House on the morning of February 15, 1851, the marshals arrested Minkins. He was the first person to be seized under the Fugitive Slave Law in New England.

News of Minkins’ arrest spread quickly in Boston’s Black community. Local abolitionist Lewis Hayden led a rush on the courthouse and helped seize Minkins from the control of the overwhelmed guards.

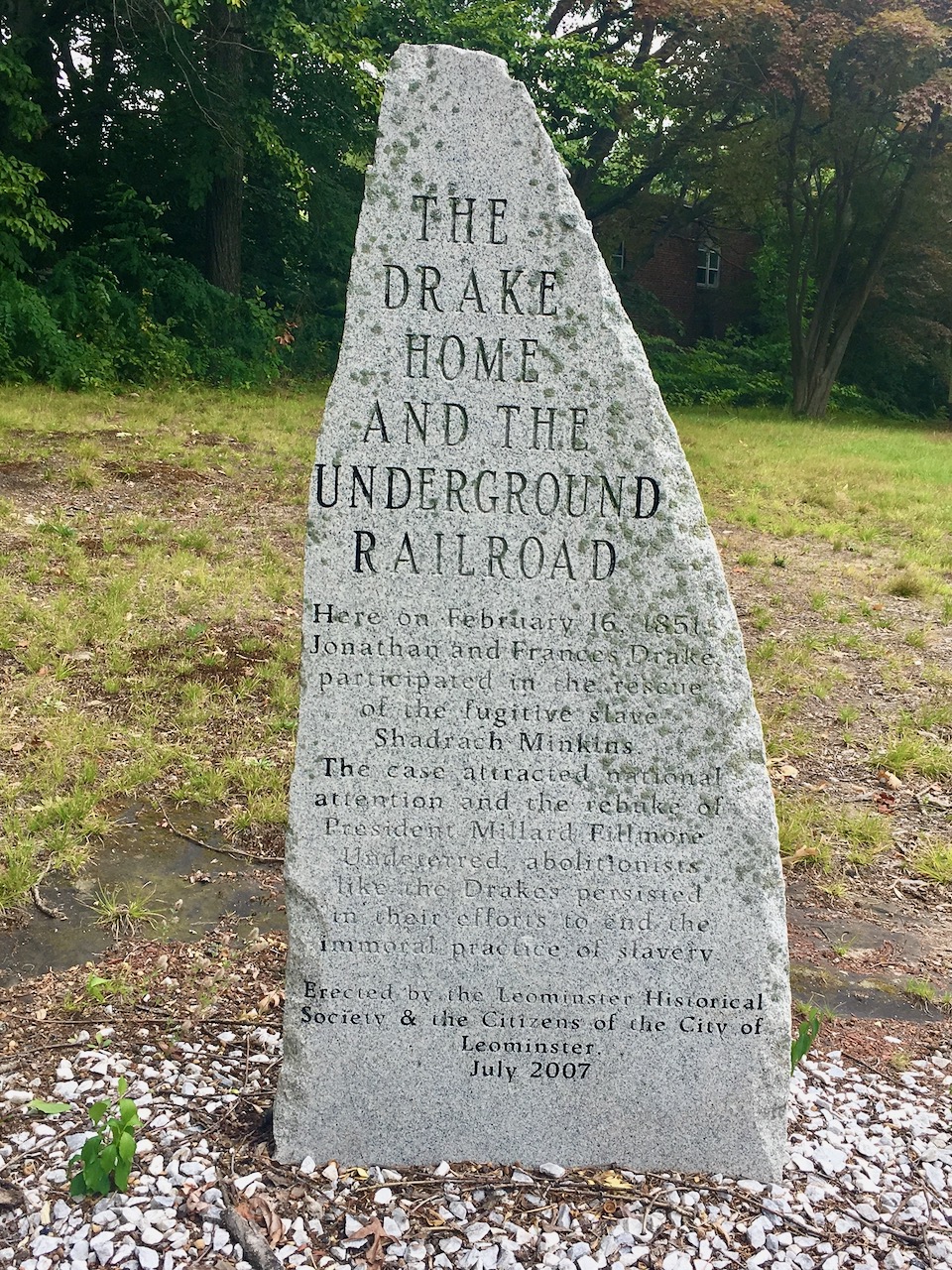

Minkins was concealed overnight in the attic of a Beacon Hill widow, then taken to the Bigelow House in Concord. The Bigelows subsequently delivered Minkins to the home of Leominster’s Frances and Jonathan Drake, where a hatch in the floorboards provided refuge for travelers on the Underground Railroad.

Frances Drake was an outspoken abolitionist who had hosted the likes of Wendell Phillips, Frederick Douglass, Charles Remond, and William Lloyd Garrison. By some accounts, Minkins disguised himself in women’s clothing and attended a Leominster anti-slavery meeting while staying with the Drakes. Frances Drake proclaimed later that she “had the honor of sheltering Shadrach when his pursuers were searching for him.”

Because the Fugitive Slave Act demanded the cooperation of free states, Canada became Minkins’ most promising option. After leaving the Drakes, he continued on through New Hampshire and Vermont, then crossed the Saint Lawrence River to arrive in Montreal.

With his newfound freedom, Minkins began a career as a waiter and barber. He met his wife, Mary, there and fathered four children. In 1860, he joined nearly forty other Canadian petitioners in a call for the creation of a Black Militia. He died a free citizen of Canada in 1875.

Sometime after leaving the Drake home, Minkins sent Frances and Jonathan a beaded purse that he had made by hand, as a thank you for their brave hospitality. The purse is now owned by the Leominster Historical Society. The Drake House was purchased by the City of the Leominster with the help of the Historical Society and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.

Learn more about Shadrach Minkins’ journey to freedom in the article, “Rescued from the Fangs of the Slave Hunter”: The Case of Shadrach Minkins and accompanying StoryMap developed by Boston African American National Historic Site.

Sources: nps.gov, Telegram.com, leominsterhistory.org