Nahum Gardner Hazard (1830 – 1913) was known to tell his children and grandchildren that a book saved his life. Although Hazard was born a free citizen in Shirley, Massachusetts in 1830, at eight years old he found himself penned at the infamous Lumpkin’s slave jail in Richmond, Virginia, also known as “the Devil’s half-acre.” Hazard was stripped of his clothing and belongings, branded on the top of his head, and subjected to the appalling conditions at Lumpkin’s, which to an eight-year-old boy were, above all else, boring. So Hazard asked for a book to read.

Due to anti-literacy laws, reading and writing skills were not commonly flaunted in places like Lumpkin’s. Hazard’s request drew the attention of a local abolitionist group, who contacted the authorities in Massachusetts. Word spread to Hazard’s parents, Emerson and Caira Boston Hazard, who had been missing their son ever since three men arrived at their doorstep and offered young Nahum an apprenticeship (either as a cattle driver or a tavern keeper in the Berkshires, accounts vary). When Hazard fell asleep on the journey, the men wrapped him in a hide and loaded him onto a train. He awoke in Richmond.

A neighbor, Major Deacon William Brown, was sent south to collect the boy and the kidnappers — Francis Wilkinson, James Shearer, and William Little — were extradited to Massachusetts to await trial. The men had also been involved in the kidnapping of another Black child, eight-year-old Sidney Francis of Worcester. Wilkinson escaped jail, Shearer was sentenced to five days of solitary confinement and seven years of hard labor, and Little was pardoned on account of his deafness.

Shortly after Hazard returned home to Shirley, his father passed away and his mother remarried, moving the family to Townsend Harbor. Hazard completed his schooling and took up work as a teamster, hauling stone. He married Harriet Phyllis of Concord in 1858. In 1861, the first shots of the American Civil War were fired.

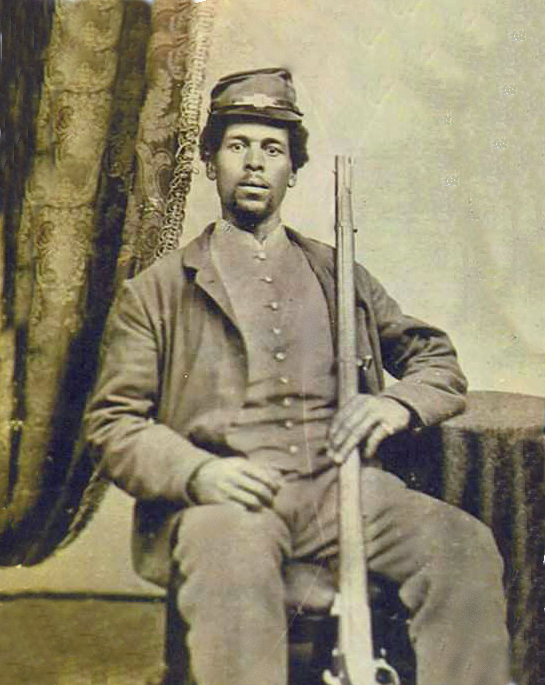

Hazard enlisted with the Union troops at Gallops Island in Boston Harbor in 1864. His brothers and several cousins had volunteered with the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, but the 54th was full by the time Hazard arrived. Instead, he joined the Massachusetts 55th Regiment, another all-Black, all-volunteer infantry.

These regiments chose to forgo their pay after the U.S. Congress declared “white” soldiers should make more money than those of color. An embarrassed Massachusetts Legislature offered to pay the difference, but the men held out until Congress reversed the decision and released their back pay.

A salary was not the only thing at stake for Hazard when he enlisted. If he had been captured, the brand still hidden under Hazard’s Union cap could have landed him back at Lumpkin’s, or worse.

Hazard evaded capture or death, but his red badge of courage, earned at the Battle of Honey Hill in 1865, was the insidious kind. Hazard was discharged back to Leominster, where he resumed work as a teamster. Unfortunately, his shoulder wound resulted in a gradual loss of use in his right arm until he could scarcely sign his own name. Even so, Hazard touted the importance of education and literacy until his death in 1913. After all, it was because of a book that so many of Hazard’s descendants still reside within the Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area today.

Sources: The Story of Nahum: Tracing a History of Black Life in America by Elizabeth Tennessee, telegram.com, archive.org

Image credit: Flickr/Bluesy Daye