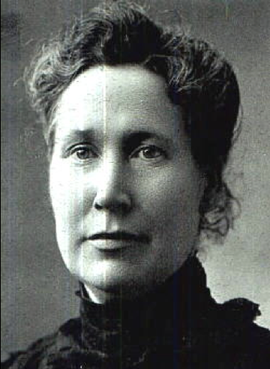

Named after her mother, Mary Kenney was born January 8, 1864, the youngest of four children to Irish immigrants who made their way west to Hannibal, Missouri by working on the railroad. At age fourteen, Mary had completed the fourth grade, “as far as any children of wage earners were expected to go.”

Following her father’s death later that year, she entered the workforce as an unpaid apprentice to a dressmaker but quickly became dismayed in the position, instead securing work in the bookbinding industry. It wasn’t long before Mary had mastered the skills of the trade, rising to the rank of forewoman. Despite working in the same position as her male counterparts, she could never earn as much as a man. This early experience with injustice and gender inequality played an important role in her decision to become a social activist to bring about change.

By 1888, Mary was the last of the Kenney children living in the area and the sole provider for her aging, disabled mother. The two moved to Chicago where Mary first got her start in organizing women into trade unions. While there, she worked with numerous individuals who were on their way to becoming prominent leaders of the Progressive Era, including Jane Addams and Florence Kelley.

Appalled by the deplorable conditions of the city, and particularly of working-class life, Mary took the lead in organizing the Chicago Women’s Bindery Workers’ Union. This was an important first step in a dynamic lifetime career as a trade union leader, which would lead to her appointment as the first woman general organizer of the American Federation of Labor by founder and president, Samuel Gompers, in 1892.

While she held that position for only a short while, Mary continued her work as a full-time union organizer for the AFL in Boston, relocating to the East Coast with her mother. There she met fellow activist and labor editor for the Boston Globe, Jack O’Sullivan. The two married in 1894 and soon began a family. Tragically, Jack was killed in an accident in 1902, leaving Mary to care for and support three young children, and her mother.

Despite all this, she focused on building relationships with middle- and upper-class women who were interested in labor issues. With the goal of educating women of the need and advantages of union organizing, she co-founded the Women’s Trade Union League in 1903 and served as its secretary for nearly a decade. She left in protest to provide relief to the textile workers of the Lawrence mills during the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912, a decision which ultimately drove a lasting wedge between the AFL and WTUL.

At the age of 50, Mary was appointed as a factory inspector by the newly commissioned Massachusetts State Board of Labor and Industries, giving her the power to enforce the laws she helped enact to improve conditions in Massachusetts’s factories just months prior. She remained in this role for 20 years, retiring in 1934. Mary lived the rest of her life in a house she had built for her family on Winthrop Street in the historic neighborhood of West Medford.

In October 1999, Mary Kenney O’Sullivan’s legacy was memorialized as one of six women portrayed in the mixed media portrait gallery “H E A R US” on the second floor of the Massachusetts State House near Doric Hall. Designed by Yale School of Art faculty members and selected from six finalists in a national search commissioned by the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, the Women’s Memorial represents the historic contributions of women to public life in Massachusetts.