The Guastavino family’s legacy is preserved in some of the most notable 20th-century buildings in the United States — not just the factory in Woburn, Massachusetts where they manufactured their signature tile, but Beaux-Arts icons like the Boston Public Library, Grand Central Station, The Biltmore Estate, and the Nebraska State Capitol. Rafael Guastavino Moreno I, followed by his son, Rafael Guastavino y Esposito II, perfected a vaulting technique that would become known as “The Guastavino Arch.” The building style remained popular until the mid-1950s when Modernist innovations in steel and concrete upset the architectural paradigm.

Guastavino’s Mediterranean technique, also known as a timbrel vault, created broad arched ceilings and domes by layering tiles in a herringbone pattern. Guastavino improved upon the design by sandwiching the tile with Portland cement, a process outlined in his 1893 treatise “Cohesive Construction.” With this advancement, Guastavino’s arches had the advantage of being strong, lightweight, economical, and — perhaps best of all — fireproof.

In the wake of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which killed 300 people, left over 100,000 residents homeless, and burned more than 3 square miles of the city, architects and city officials were searching for safer, more fire-resistant building technologies. In light of this, a young Spanish innovator in fireproof building, Rafael Guastavino, was invited to present at the 1876 World Exhibition in Philadelphia. Though he spoke little English, Guastavino sensed a business opportunity and in 1881 he immigrated to the U.S. with his 9-year-old son in tow.

In 1889, Guastavino landed his first major commission, engineering the Boston Public Library’s Copley Square Branch for the lauded architects McKim, Mead, and White. Shortly after, Guastavino founded the Fireproof Construction Company (which would later become the R. Guastavino Company).

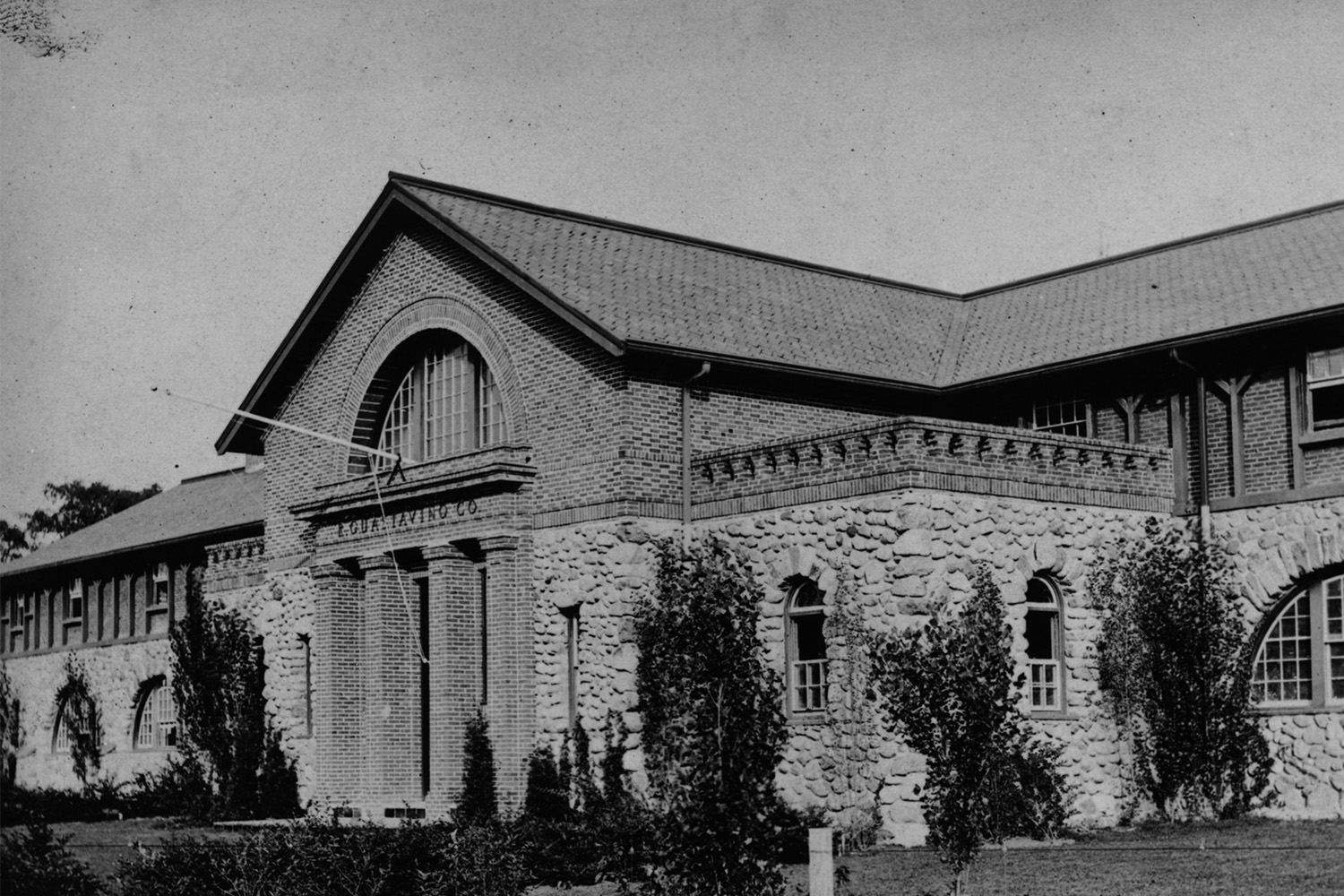

The Boston Public Library earned Guastavino considerable recognition, and commissions poured in for public spaces across Massachusetts and New York. In order to keep up with the demand for tile, Guastavino opted to build his own production facility. His financial advisor recommended his hometown of Woburn, Massachusetts, where Guastavino set up in an out-of-use church. By 1903, the church was producing over 200,000 tiles annually, cementing the need for a larger facility. Guastavino turned to his son, budding engineer Rafael Guastavino y Esposito II, to design the new Guastavino tile factory.

Guastavino II would follow closely in his father’s footsteps, helping to expand the company’s name throughout the U.S. Together, the Gaustavinos garnered 24 patents for processes related to cohesive construction and tiles. Their work graced hundreds of buildings across the country — many of which are now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Guastavino story came full circle in 1917, when Guastavino II was commissioned to rebuild the Ellis Island Great Hall — the very gateway to America he had passed through as a nine-year-old boy. The Hall is an impressive feat, consisting of 28,832 tiles interlocked into a self-supporting 17-meter-high vault. The Guastavino arches proved so strong that when the Great Hall was restored in the 1980s, only a few tiles required replacement.

Learn more about Guastavino’s life and work on the Guastavino Alliance website.

Sources: wikipedia.org, tocci.com, rguastavino.org

Photo caption: Designed by Guastavino II in 1903, the Guastavino Tile Factory was built in Woburn, Massachusetts as production at the company’s makeshift factory in a former church nearby soared to 200,000+ tiles annually. In a 1907 dedication, a local Woburn paper described it as “an ornamental brick building that looks more like an art museum than a factory” — much to the delight of the stylish Guastavinos. Image courtesy of TOCCI