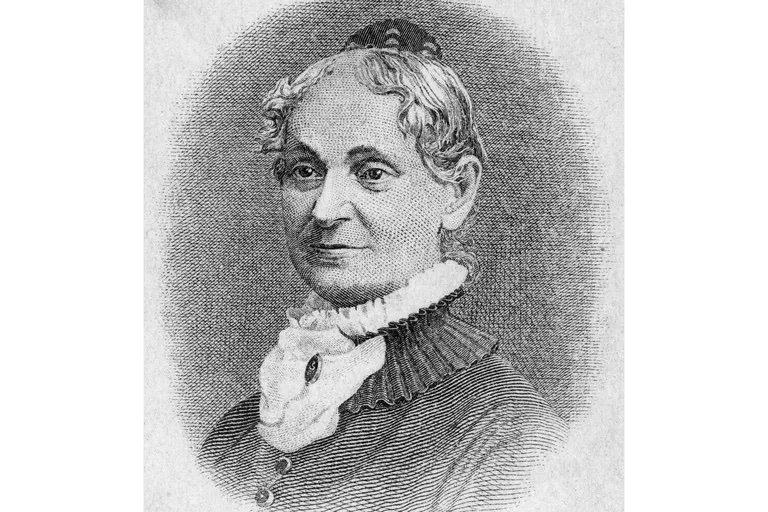

Born in 1819 in the manufacturing city of Lynn, Massachusetts, Lydia Estes Pinkham (1819-1883) is best known for the development of her medicinal “women’s tonic,” which she grew into a successful business through her shrewd marketing talents.

One of twelve children, she was the daughter of William Estes, a prominent Quaker who had risen to the status of gentleman farmer through his fortunate dealings in real estate. Supporters of abolition, neighbor Frederick Douglass and other prominent abolitionists were often guests in their home. The family would eventually break with the Quakers over the issue of slavery in 1830. Pinkham attended Lynn Academy and at age sixteen was active in the Lynn Anti-Slavery Women’s Society. She worked as a teacher until her marriage to Charles Hacker Pinkham in 1844 and continued to support feminism.

Like many women of the era, Pinkham brewed home remedies, collecting herbs and other ingredients for her recipes. With medical fees often too expensive in other than an emergency, people often turned to these alternatives, which could as easily kill as cure. With the her husband’s family fortune in ruins, Pinkham began to accept payments for her remedy for female complaints. Begun on her family stove, its success grew to enable factory production with all four of her children involved in the business.

Lunenburg, Massachusetts lays claim to some of the fame surrounding Lydia E. Pinkham as she lived for a short period of time on Northfield Road in the former Arnold Dickinson house. The manufacture of her compound began from the roots gathered at Mulpus Brook. Originally the recipe was comprised of five herbs and some drinking alcohol. Black Cohash, one of the ingredients, is an accepted alternative hormonal treatment. While still available today, the advent of the Food and Drug Administration necessitated changes in the formula.

In 1876, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound became one of the best-known patent medicines of the 19th century. She skillfully marketed her product directly to women, a practice that continued after her death. Her face on the label and her keen use of the testimonials of grateful women furthered her success. Advertising urged women to write her, and they received answers from her, and later her employees even decades after her death. Information and advice on women’s medical issues was shared along with encouragement to use her product.

While her motives were economic in promoting her compound, her distribution of information on the “facts of life” to a population poorly served by the medical community, has modern-day feminists admiring her as a crusader for women’s health.

Source: Wikipedia, Town of Lunenburg