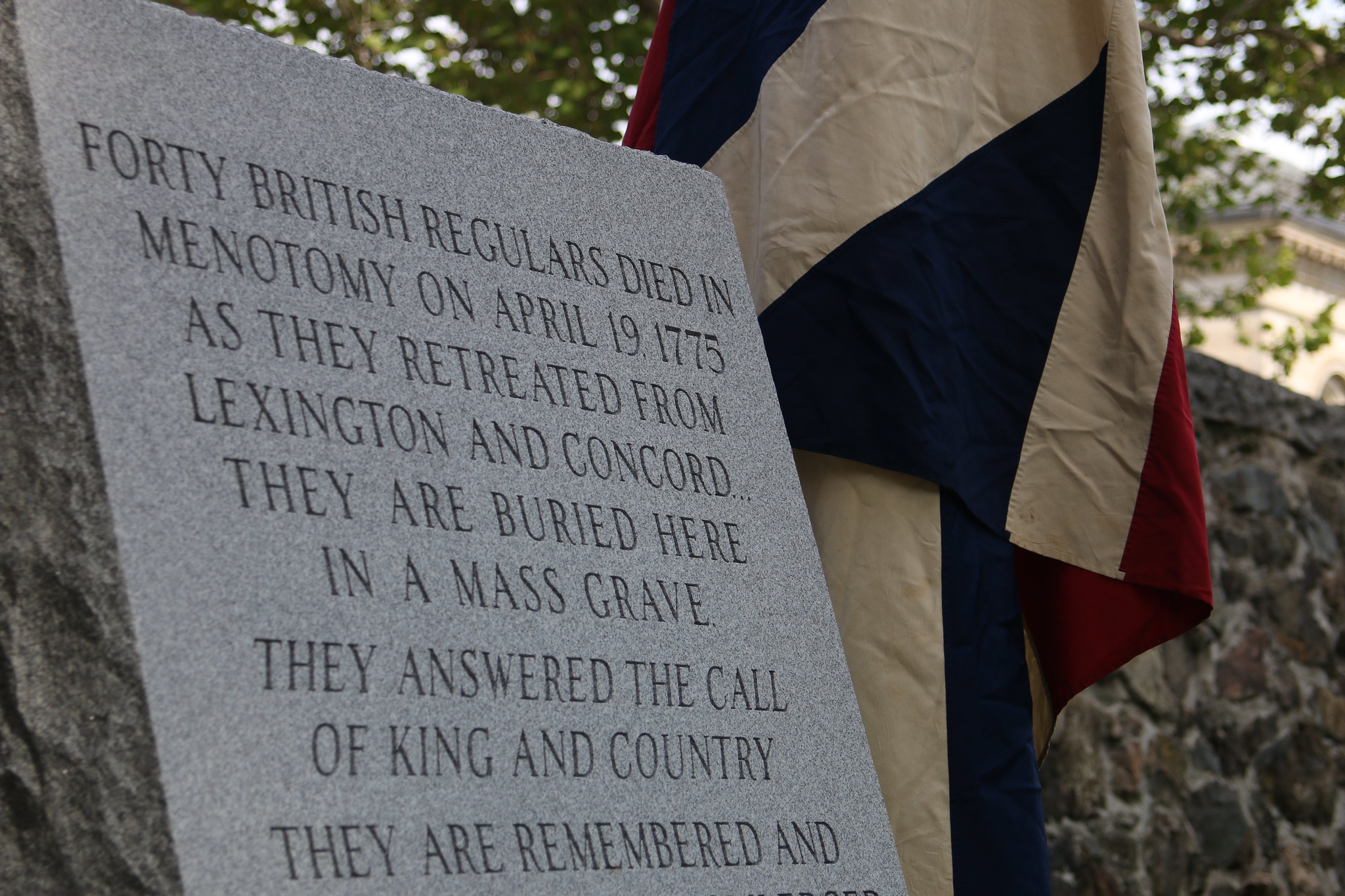

Approximately 24,000 to 25,000 British soldiers are estimated to have died over the course of the American Revolution. While about half of the British forces were loyalists who lived in the colonies, the other half was composed of soldiers who had traveled overseas. Considering the impossible cost and logistics of sending the deceased soldiers home, British Army regulations called for the dead to be buried onsite at the battlefields. Throughout New England, there are examples of this phenomenon, from mass graves in Arlington and Boston to single burial sites along Concord’s Battle Road. The sites in Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area reflect the casualties of the fighting in Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, and Menotomy (present day Arlington) on April 19, 1775. But it’s the stories of how these graves were treated — whether they went unmarked or memorialized, honored or ignored — that shed light on how feelings about British soldiers have changed with the zeitgeist.

At the time of interment, most British graves did not include any names or identifying information. In some cases, the graves went entirely unmarked. That’s not to say all colonists were dispassionate about the deaths of British soldiers. As one local story goes: when five British soldiers who were killed in a skirmish near the Hartwell Tavern were transported to the Lincoln Town Cemetery, Elizabeth Hartwell insisted that they be buried in her family plot. She was the sole mourner at their funeral.

Still, even those graves were treated strangely by modern standards. As Henry David Thoreau wrote in a recap of his 1850 visit to Lincoln Cemetery, a phrenologist named Walton Felch reached out to the Lincoln Select Board for permission to exhume two British skulls from the plot. Permission was granted, and Felch reportedly used the skulls in his well-known traveling demonstrations until his death, by which point phrenology, and the possession of human skulls, had fallen out of favor. While one skull remains at large, the other is thought to have been buried discreetly at another grave of two British soldiers near the North Bridge in Concord.

It wasn’t until after the centennial of the war that communities began memorializing British graves in earnest. In 1884, the Town of Lincoln placed an inscribed stone on the graves of the five British soldiers. In 1905, the Lexington Historical Society placed a marker at the Old Burying Ground.

By the turn of the 21st century, there was a renewed interest in memorializing British burial sites. In 2000, the Town of Concord placed a marker on Monument Street for a soldier who had died of wounds following the retreat from North Bridge. The same year, the National Park Service erected granite markers at six burial sites along the newly completed Battle Road Trail.

Today, these sites are integrated into Patriots’ Day ceremonies and other commemorations of the bloody day that began the American Revolution. The decision to formally memorialize British burial sites indicates that with the passage of time, more and more Americans have arrived at the same empathetic sentiment as Elizabeth Hartwell: That these young men, far from home, who sacrificed themselves for their country, deserved to be laid to rest with dignity.

Image credit: Doug Klostermann