We all know the top-hatted figure of Uncle Sam, usually depicted with a white beard and a star-spangled suit. But before he was a military poster or a political cartoon, was Uncle Sam a real person? In our latest “A Closer Look,” we dive into the story of Arlington-born Revolutionary War patriot Samuel Wilson, and how his role as a meatpacker during the War of 1812 may have inspired one of America’s most lasting cultural icons.

The image of Uncle Sam was first popularized by Harper’s Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast, who also created iconography like the modern Santa Claus and the donkey and elephant symbols to represent American political parties. By the time the white-bearded, stars-and-stripes-clad figure appeared on James Montgomery Flagg’s “I want you” military recruiting poster in 1917, Uncle Sam had become a staple of American pop culture. Historians don’t always agree on when Uncle Sam first came to represent the United States government, but the prevailing legend dates back to the War of 1812 and a well-known meatpacker named Samuel Wilson.

Samuel Wilson was born in Arlington, Massachusetts and grew up in Mason, New Hampshire. At fifteen years old, he joined the American Revolution, where he was charged with overseeing cattle and packing meat.

That experience would prove crucial years later when Samuel and his brother Ebeneezer moved to the Hudson River city of Troy, New York. The brothers formed a meatpacking company called E. & S. Wilson, and Samuel became well-known in the area as a business person, town assessor, and road commissioner. Locals affectionately referred to Wilson as their friendly “Uncle Sam.”

When the U.S. declared war against British North America (Canada) in 1812, E. & S. Wilson became a key supplier of provisions to the U.S. military. They contracted with Elbert Anderson Jr. to issue rations to troops throughout New York and New Jersey. E. & S. Wilson’s strategic location on the Hudson River made it easy to ship the 2,000 barrels of pork and 3,000 barrels of beef. During this time, Samuel Wilson was also appointed as a meat inspector for the U.S. Army.

In keeping with shipping regulations, all rations were stamped “E.A. / U.S.” to signify the contractor’s name (Elbert Anderson) and the country from which they had originated (the United States). However, local ferrymen, teamsters, and military personnel knew that the meat had originated from E. & S. Wilson and they began joking that the “U.S.” on the barrels was the mark of their beloved Uncle Sam.

The joke caught on and soon the appellation “Uncle Sam” became synonymous with the United States government. The New-York Gazette first reported the story of “Uncle Sam” Wilson in 1830. For political cartoonists like Nast in the 1850s, Uncle Sam was a convenient personification of federal power that could be used for both proud nationalism and scathing satire.

The name and image of Uncle Sam are still widely used today. And while some accounts cast doubt that Samuel Wilson was indeed the Uncle Sam, a burst of anti-communist patriotism in 1961 caused Congress to pass a resolution declaring “‘Uncle Sam’ Wilson, of Troy, New York, [the] progenitor of America’s national symbol of ‘Uncle Sam.’”

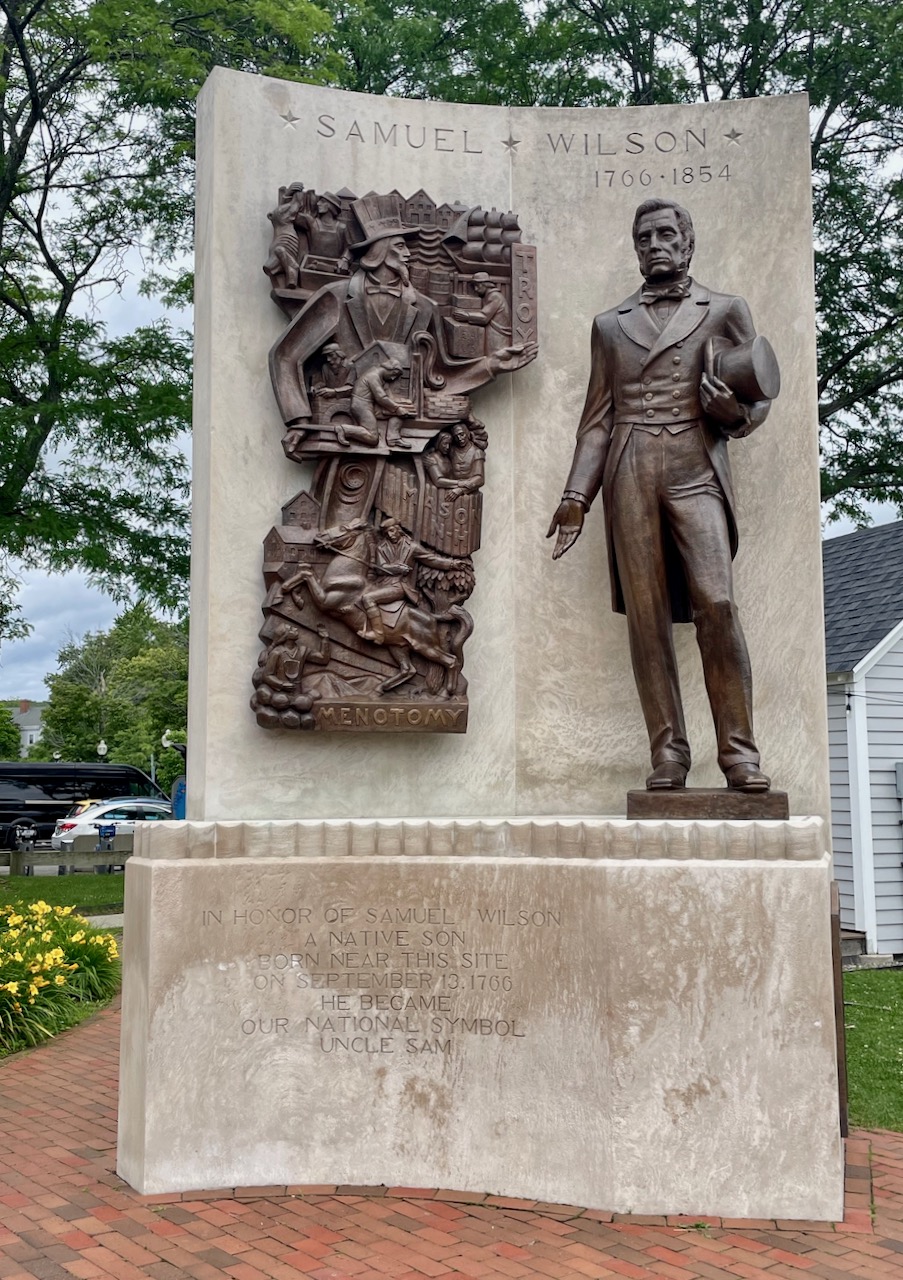

Here in Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area, the towns of Arlington, MA and Mason, NH have come to acknowledge their roles as the home of Uncle Sam. A plaque recognizes Uncle Sam’s childhood house in Mason, while a statue in the center of Arlington commemorates Uncle Sam’s birthplace.

It seems the Congressional resolution has forever cemented Samuel Wilson’s ties to one of the most ubiquitous cultural icons to represent the United States of America.

Sources: Exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov, history.com, memory.loc.gov, govinfo.gov